Henry S. Whitehead (1882-1932) is remembered primarily for

his short stories, many of which were originally published in Weird Tales magazine in the 1920s and

early 1930s and collected posthumously in two volumes published by Arkham

House, Jumbee and Other Uncanny Tales (1944)

and West India Lights (1946). Less known is the fact that Whitehead

published two books during his lifetime, the first being a work of populist

theology, The Garden of the Lord

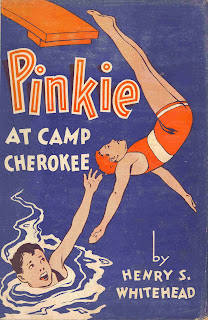

(1922), the second being a novel for boys, Pinkie

at Camp Cherokee.

In the

1920s, Whitehead was involved with a number of summer camps for boys, and he

was one of the owners of Camp Cherokee on Long Island,

so in one sense his novel can be viewed as a kind of advertisement for the

camp. Whitehead’s first story for boys, “Baseball and Pelicans,” had been

submitted to Clayton H. Ernst, editor of The

Open Road for Boys, and it was published in the June 1926 issue. Ernst told Whitehead that he should write a

book around the tale, and Whitehead took up this advice during the winter of

1929-30 while he was ill. The two main episodes in Whitehead’s short story were

expanded into a novel titled Pinkie—Superguy. The title was sensibly changed by the

publisher to Pinkie at Camp Cherokee.

It centers around a young red-haired boy from Barbados named James Roderick

Evelyn Maurice Kelley-Clutton, who is nicknamed Pinkie because his skin turns

pink rather than tan when exposed to the sun. The story is told by a regular

boy Bill Spofford from Pencilville,

Ohio. Pinkie, with his British

accent and complete lack of knowledge of regular American traditions, serves as

the proverbial fish out-of-water, and an object of ridicule for most of the

boys at the camp, until they come to realize that not only is he talented—his

running abilities win a competition, and his unorthodox batting, cricket-style,

wins a baseball game—but worthy of their respect and friendship. Of course rivalries between campers and other

nearby camps are presented in a simplistic us/good versus them/bad mentality,

and the chumminess between the friendly boys is often cloying and

sentimentalized. The attitudes are dated, and the whole book would be a dire

read save for two stories inserted as tales told to groups of boys. In one (pages 83-90), Pinkie tells a story

around a campfire of a West Indies negro superstition about acquiring luck from

a Dead Man’s Tooth. In the second (page 148-158), the camp Chief

tells the weird life-story of a thin match.

Remarkably, this tale appeared in a slightly different and longer form

as “The Thin Match” in the March 1925 issue of Weird Tales. These two inserted tales account for the only value of

this book to the modern reader.

I'd also like to call attention here to an article by David Goudsward coming out later this month in The Weird Fiction Review, no. 4, from Centipede Press. Goudsward's article is called "Halsey and the Padré: A 14-year-old’s perspective on H. S. Whitehead". The article shows a side of Whitehead's personality not usually explored, that of his role at a boys' summer camp.

And another piece of Whitehead lore includes the following photograph, originally published in The New York Times, for Sunday, January 26th 1930. Upon seeing it Whitehead was inspired to write a letter to twelve-year-old Teddy Gants, the second figure from the left.

Dear Mr. Teddy Gants,

I noticed your picture in the N.Y. Times of Sunday, January 26th, and as I looked at it I said to myself: "There's exactly the kind of boy I want in my camp!"

So it occurred to me to drop you a line and ask if you go to camp summers, or if, perhaps, you might be interested in Pine Bluff Camp at Port Jefferson, Long Island. Pine Bluff is a mighty fine camp, with more than 100 boys, and a good place for an athlete. I've always been one, all my life, and was three years a Metropolitan District (N.Y.) Sr. Champion All-Around athlete.

Maybe if you, or your father or mother, are interested in your going to camp, you might drop me a line, and I can have the catalogue sent to you, etc. Or, if you will let me know your home address I can come in and talk it over when I come north. It won't be very long now.

We have everything at Pine Bluff from handball up and down!

Best wishes,

Very sincerely yours,

Henry S. Whitehead

Teddy Gants, a twelve-year-old girl, noted of the letter, "Say, I wonder what kind of person that man thinks I am." But that question should really be directed toward the letter-writer.

Mildred Mangold (second from right) really lives up to her surname. But perhaps we should blame the photographer for such an unflattering portrait of all those young skaters.

ReplyDelete