There is a great deal of enjoyment in reading old books about wanderings in Britain. There is, to begin, the interest in how they did things differently then. Then, there are usually unexpected sidelights on history and folklore, sometimes with customs and traditions otherwise unrecorded. We might hope for evocations of landscape, in all weathers, with an atmosphere sometimes like that found at the outset of ghost stories or supernatural thrillers.

The essence of the approach in this kind of book is that it is rambling and ruminatory. Such books don’t really have a useful descriptive term of their own. They are, to be sure, often found in the travel and topography shelves of second-hand bookshops, but here they also mingle with the brisker and more practical sort of guide book. Though they might sometimes even be presented as guides of a sort, they are not at all the same kind of thing. A sure sign is that the author has to keep recalling themselves to their supposed task of providing useful information, after wandering off both literally from their route and metaphorically from mere fact-giving into remoter regions of thought.

A fine example came to me, suitably enough, by a winding path. In a catalogue at the back of a book by H A Vachell, there was an announcement of a new 1930 novel by William Ellis, Ascetic. The descriptions of titles at the back of books are frequently diverting: some go into so much detail you feel you no longer need to read the book; others are vapid and vague; some provoke hilarity by their very incongruity.

William Ellis’ first novel, Beloved River (1930), this note said, was regarded as full of promise, not least for the ‘exquisite writing’, and Ascetic, the new one, added to this ‘beauty and deep sincerity’. The phrases were alluring enough, so I looked into him. Ellis proved to have issued six books in all, in the period 1930-1940. There were four novels, a translation, and a travel book. As it turned out, I couldn’t at first get any of the novels, but I did find Journey Westward, The Record of a Tour in the Welsh Marches—and Beyond (1940), his last known book.

This is about a motor tour of the Welsh border lands from South to North, with his wife, taking their chances at wayside inns and small-town hotels. It takes place just before and just after the outbreak of World War Two in 1939, and has a somewhat valedictory air, as if the country is being seen at a particular moment that will never be the same again.

At Caerleon he is shown the Tennyson Room, where the great poet quartered while researching the Arthurian legends for his ‘Idylls of the King’ (as Arthur Machen also recalled). At Llanthony Abbey he remembers how he came this way many years ago when he crossed the Black Mountains on a walking tour aged 17. Seeking shelter in a storm, he found an old man and a boy in a shack, and shared a windfall of apples in his knapsack with them. In return, seeing he is a scholar, they give him a big black book (in fact rather a nuisance to carry), which turns out to be a breeches Bible. But now, he finds, the Abbey hotel is full of suave, sporty individuals in sleek cars.

Visiting the village of Newcastle, he knows already of folklore associated with the place: a fairy oak and a holy well, but finds that these are now of no interest to the inhabitants. The young people he meets want the pictures, dance bands on the wireless, cocktails, the older ones obsess over the football pools.

However, he is still diverted by curiosities found on the way: the story of John of Kent, Franciscan friar and magician, who was not from Kent, but from these parts; the elephant stabled in winter quarters at the inn in Bishop’s Castle and fed buns by the local schoolchildren; the old bassoon preserved in Montgomery church; the tame jackdaw in Rhayader ‘that was the biggest thief in Wales and might well have outdone his fellow in Rheims if only he could have found a chronicler.’ Alas, he finds ‘from the few inquiries I made, it appears that he is gone and his exploits forgotten.’

At the sequestered village of Clun, Shropshire, Ellis was once told by the girl in the sweet-shop of two taboos he must observe as he crosses the bridge over the river: he must not utter a word and he must look straight ahead and not to either side. These so impressed him that he decided he must write a novel called The Bridge of Clun. But his publishers did not like it; so he rewrote the second half; and they still didn’t like it, so he rewrote the first, and in the end it was issued under a pseudonym, and by then not much of the bridge at Clun was left in it. This must be, I suppose, his Farewell to Poaching, as by William Cumming (Selwyn & Blount, 1933).

On some occasions he seems to stray into idyllic country. ‘If anything that I should write persuades anyone to travel this way, I pray them not to ignore the narrow lane to Cwmyoy,’ he writes, ‘but to visit this church and discover its quaintness and beauty for themselves.’ This little village, in the far Northern tip of Monmouthshire, the ancient kingdom of Gwent, remains remote today. The church is noted for its crooked tower. Later he writes of ‘the quietest, greenest valley that a man could find. Lost in the centre of it is the hamlet of Dulas . . . As for Dulas itself, it is one of those villages which really isn’t there . . .as quiet and dreamy a spot as any.’

This sort of country wins his heart but as he approaches the final Northern part of his tour he decides not to continue, finding the landscape too busy, too plain. He tells us: ‘Of Wrexham I have a particular horror since the afternoon when I addressed a meeting in a Church hall under the auspices of the True Law party, to which I was acting as organising secretary.’ The booked speaker had not come, so he was obliged to fill in. Whether Ellis worked for them in a purely professional capacity or from conviction is not clear.

What was this party, unknown to Parliament or to electoral history? It seems to have been the creation of one David Hamshere of London, calling for a politics guided by biblical precepts and seeking to build a ‘Holy British Empire’. Hamshere published a 221pp book, We Need Mosaic Law Now (T Werner Laurie, 1935): and a 36pp pamphlet entitled The True Law Party was issued from London in 1936; and then silence.

And what became of William Ellis after he wrote this book I do not know. There is an oblique allusion that may suggest he had some sort of illness, and in any case by the time his book ends the clouds of war are massing on the horizon. But he is a zestful, piquant and companionable writer, with some of the same love of the quaint and curious and old traditions found in Arthur Machen’s essays and autobiographies.

(Mark Valentine)

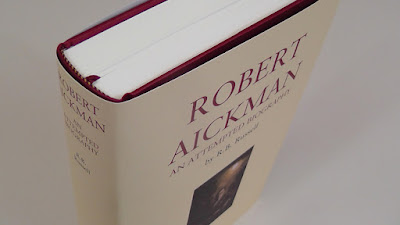

Image: Cwmyoy church, from the Brecon Beacons National Park website