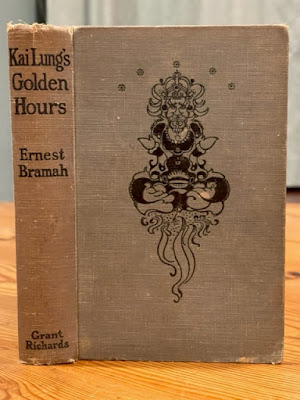

Today marks the centenary of Ernest Bramah’s Kai Lung’s Golden Hours (1922), the second volume in his series about a wily Chinese storyteller, following The Wallet of Kai Lung (1900). Doug Anderson has identified that the UK edition was published on 30 October 1922. The book uses the Scheherazade device of stories told before a potentate to postpone a fatal sentence.

The Kai Lung stories are noted for a highly ornate, courteous and circumlocutory form of dialogue intended to suggest the formalities of Mandarin in English. Each episode also has a title in similar elevated form. The adventures of Kai Lung, however, are straight out of traditional storytelling, typically involving wicked overlords, cunning courtiers, magicians, bandits, mendicants and lovely (and resourceful) young women.

Bramah achieves a comic contrast between the loftiness of the language and the often rather base motives of his characters, which include avarice, ambition, lust and revenge.

The style was an elaborate invention of Bramah’s, who had in fact never been to China, and his depiction of its landscape, legends and customs is purely a fairy-tale, willow-pattern fantasy. The only remote comparisons would perhaps be to the heightened prose and sardonic undercurrents of Lord Dunsany’s tales, or the contrast between the omniscient Jeeves and the jejune Wooster in P G Wodehouse’s tales.

I found my own copies of the first three volumes in a catalogue from the late and much-missed Manchester fantasy/SF bookdealer Mike Don of Dreamberry Wine, as I did so many other good things. They were cheap reprints in golden covers and very battered, half-torn dustwrappers, but they were a passport to some hours of pleasant reading. I went on to pursue other books by Bramah and to write about him for Book & Magazine Collector. I was delighted to find that William Charlton, co-author of the first Arthur Machen biography (with Aidan Reynolds, 1963) was also an aficionado and had in fact acquired Bramah’s copyrights.

The Kai Lung books were a great favourite of Edwardian and interwar literati, including Hilaire Belloc, who provided a preface to the Golden Hours, J.C. Squire and Dorothy L Sayers, who has Lord Peter Wimsey quote Kai Lung several times. Belloc recounts his pleasure at the first book in the series, and says he has ‘just over a dozen’ copies in his house and that he has frequently presented it to friends.

The new book, he avers, has ‘the same complete satisfaction in the reading’. Quoting a few of what were to become much-admired phrases, he challenges doubters to ‘try to write that kind of thing yourself’. Belloc believes the books will endure: ‘Rock stands and mud washes away’. The book has indeed been reprinted numerous times, including as a Penguin paperback, in Richards Press reprints, and in Lin Carter’s Pan Ballantine Adult Fantasy paperback series in 1972.

Ernest Bramah, who was an enigmatic and reclusive figure, possibly felt somewhat haunted by his character and the frequent demand for more of his adventures. The Golden Hours was followed by Kai Lung Unrolls His Mat (1928), The Moon of Much Gladness (1932), a novel presented as narrated by Kai Lung, and Kai Lung Beneath the Mulberry Tree (1940). Kai Lung: Six (1974) offers previously uncollected tales.

It is certainly true that the Kai Lung stories will not be everyone’s cup of Keemun, but those who acquire the taste will soon be pursuing them all with, to quote from the Golden Hours, “the unstudied haste of one who has inconvenienced a scorpion”.

(Mark Valentine)