Some years ago, the National Centre for Early Music in York, situated in the converted church of St Margaret, ran a series of concerts under the heading ‘Late Music’, offering work by contemporary composers. At a performance of songs for solo voice and piano accompaniment, I was surprised and delighted to find there were several pieces setting verses by E H Visiak.

Visiak (1878-1972) was an early champion of David Lindsay (whom he befriended), the author of the fantastical seafaring romance Medusa (1929), and of other very strange fiction, and an eminent Milton scholar. But his early work was as a poet. He published five main volumes: Buccaneer Ballads (1910); Flints and Flashes (1911); The Phantom Ship (1912); The Battle Fiends (1916); and Brief Poems (1919).

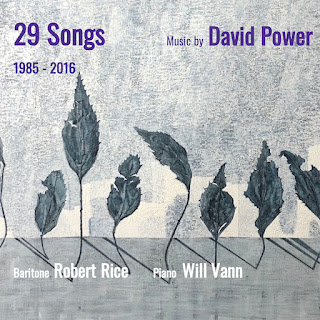

The composer of the pieces I had heard was David Power, also a notable Lindsay scholar, and I am pleased to report that a selection of his work has now been issued on the Prima Facie label, entitled 29 Songs, 1985-2016, performed by Robert Rice (baritone) and William Vann (piano). They include not only five pieces based on Visiak poems, but others setting work by Walter de la Mare, Robert Louis Stevenson and Ronald Duncan.

It was also a pleasure to see three songs from pieces by the late Paul Newman, editor of the journal Abraxas, biographer of Frank Baker, authority on White Horse hill figures and lost gods, Wormwood contributor, and much else besides. There are also works by other contemporary poets. Each of the pieces is brief, a few minutes at most, but achieve an admirable concentration of character.

In the accompanying booklet, David Power records that he first discovered Visiak through Colin Wilson’s book Eagle and Earwig, then greatly enjoyed Visiak’s autobiography Life’s Morning Hour. He agreed with Wilson that Visiak ‘had a gift of writing about things as if seeing them for the first time and brought an almost visionary freshness to ordinary things.’ This inspired him to set some of his poems to music.

The Visiak songs here include ‘An Old Song’, with Satie like piano and a delicate, wistful melody; ‘Passion’, with the urgency and tumult suited to its theme; and ‘The Shipwreck’, grave, slow, elegiac. The setting of Ronald Duncan’s ‘Remember Me’ has a gentle, haunting melody, while the four de la Mare pieces capture the uncanny, nursery-rhyme oddity of his verses (from Peacock Pie), especially in the terse, tripping melody of ‘Five Eyes’. Paul Newman’s humorous ‘In my More Thoughtful Moments’ (‘I can feel sorry/For the Four Horsemen/Who never halt/ At an inn’) has a jaunty treatment capturing its tone.

In their commitment to mystery and their angular individuality, the songs seem to me to have an affinity with the piano works of Charles-Valentin Alkan. The album is thoroughly engrossing, offering unusual selections and achieving an aura of the singular and strange.

(Mark Valentine)