I first looked into the books of Michael Maurice because I had read a description of his The Last House (1933) in a publisher’s catalogue at the back of a book which said it was about a semi-independent enclave in Britain. This sounded as if it might be like two books I enjoyed with a similar theme, The King of Lamrock (1921) by V Y Hewson and Old King Cole (1936) by Edward Shanks.

There are points in common: all three involve temperamental squires possessive of their traditions and rights, in remote corners of the country. But Maurice’s novel is predominantly a conventional social comedy, even to the extent of involving a nurse-and-patient romance.

There are picturesque aspects: the protagonist is a speechwriter and ghost-writer, both for eminent personages and for eccentrics, and the author has some fun with this; but essentially this is a whimsical satire. It was praised by J B Priestley and is very much in his style. The theme presages the Powell & Pressburger film A Canterbury Tale (1944), also with an old-fashioned and domineering squire.

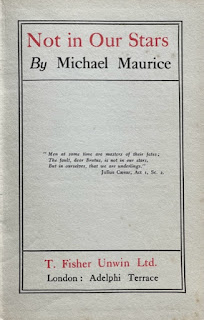

Maurice’s first novel, Not in Our Stars (1923), which celebrates its centenary this month, starts interestingly enough. The tone is that of the society novel, but the content rather Wellsian, an odd mix. Menzies, a saturnine clubman, has second sight, though he cannot use it at will: it occurs seemingly randomly and lasts about an hour or so.

He is convinced by this that we are all predestined: that we simply follow a thread of fate already wound out for us. At a dinner party there is discussion of a recent meteor strike in the Andes, and an earlier one on the coast of Greenland: Menzies predicts even more dramatic collisions to come, which may shift the Earth off its axis.

We soon witness just such a great upheaval and a descent of darkness, and after this Menzies wakes up in a new scene entirely, and a rather desperate one. He is, in fact, now living backwards, his days preceding, not succeeding, each other. Though this is a neat idea, and Maurice handles it very capably, he unfortunately plays it out through a conventional and melodramatic plot that rather undermines his earlier inventiveness.

Not in Our Stars was published in the Fisher Unwin First Novel series, and it looks as though Maurice was trying to make his book as winningly commercial as possible, to get the attention of the publisher. The time-twisting element is bold and interestingly speculative but the use of it a bit too garish.

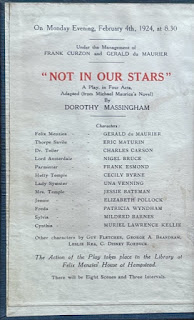

My copy of the book (once priced at half a crown) bears the ownership rubber stamp mark of Wyndham’s Theatre Box Office Manager, with a signature, and on the fixed front endpaper a playbill is pasted in, showing that a dramatisation of the book by Dorothy Massingham was performed ‘On Monday Evening, February 24th, 1924, at 8.30’. The cast included Gerald du Maurier (as Menzies), Eric Maturin and Nigel Bruce.

Michael Maurice was the pen-name of Conrad Arthur Skinner (1889-1975), a Methodist minister and for many years the chaplain at the Leys School, Cambridge: he had been a cox in the university boating team. He was the author of ten novels in all, including others with supernatural content, but those that I have read so far all seem to have this somewhat overly-calculated commercial slant.

This is odd, because Maurice himself praised the work of J.D. Beresford, whose novels are quite the opposite: thoughtful, steady, slow-burning, almost too subdued. I am therefore hoping that there might turn out to be one or two of Maurice’s books that allow his unusual ideas to prevail rather more.

(Mark Valentine)

Did you mean "picaresque" instead of "picturesque"?

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteThank you, but no - it isn't a picaresque. I meant that it has some vivid portraits and scenes. Mark V

Delete